| ||

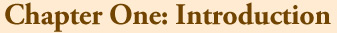

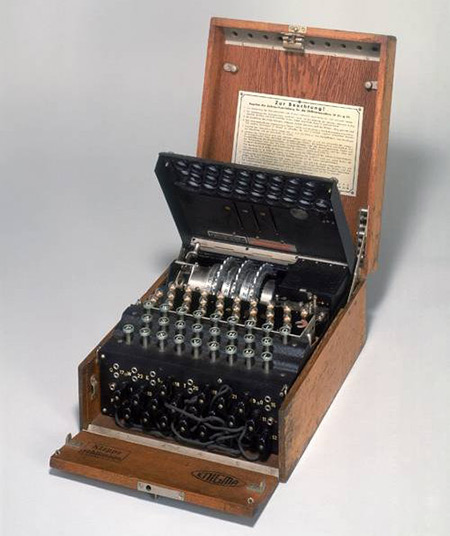

The story of the Enigma cipher machine and its defeat by the Bletchley Park codebreakers astounded the world. This book describes Bletchley’s success against a later, more advanced German cipher machine that the British codenamed Tunny. How Bletchley Park broke Tunny has been a closely guarded secret since the end of the war. Unlike Enigma, which dated from 1923 and was marketed openly throughout Europe, the ultra-secret Tunny was created by scientists of Hitler’s Third Reich for use by the German Wehrmacht. Tunny was technologically more sophisticated than Enigma and—theoretically—more secure. From 1942 Hitler and the German High Command in Berlin relied increasingly on Tunny to protect their communications with Army Group commanders across Europe. The Tunny network carried the highest grade of intelligence. Tunny messages sent by radio were first intercepted by the British in June 1941. After a year-long struggle with the new cipher, Bletchley Park had its first successes against Tunny in 1942. Broken Tunny messages contained intelligence which changed the course of the war, saving an incalculable number of lives. Central to the Bletchley attack on Tunny was Colossus, the world’s first large-scale electronic digital computer. The first Colossus was built during 1943 by Thomas H. Flowers and his team of engineers and wiremen, a tight knit group who worked in utmost secrecy and at terrific speed.1 The construction of the machine took them ten months, working day and night, pushing themselves until (as Flowers said) their “eyes dropped out”.2 The racks of complex electronic equipment were transferred from Flowers’ laboratory at Dollis Hill in London to Bletchley Park, where Colossus was reassembled. Despite the fact that no such machine had previously been attempted, the computer was in working order almost straight away and ready to begin its fast-paced attack on the German messages. The name “Colossus” was certainly apt. Colossus was the size of a room and weighed approximately a ton. By the end of the war in Europe there were ten Colossi working at Bletchley Park. The computers were housed in two vast steel-framed buildings—a factory dedicated to breaking Tunny. There are more photographs of the Colossi elsewhere on this website … read the amazing story of Colossus online. Shortly after Germany fell, Winston Churchill ordered that most of the Colossi be broken up. Two were retained by the peace-time descendant of Bletchley Park, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). Details of their postwar use have not been disclosed. The last Colossus is believed to have stopped running in 1960. The war over, key Bletchley personnel moved to Manchester University. Various of the electronic panels from dismantled Colossi were taken to the newly created Computing Machine Laboratory there, although not before every trace of their original purpose had been removed. Colossus itself was a special-purpose computer, custom-built for codebreaking. In June 1948, in the Computing Machine Laboratory, the world’s first truly general-purpose electronic digital computer ran its first program. Soon a Manchester engineering company developed the university’s rough-and-ready prototype into the Ferranti Mark I, the first electronic digital computer to go on the market. It was the start of a new era. All involved with Colossus and the breaking of Tunny were gagged by the Official Secrets Act. The very existence of Colossus was classified. A long time passed before the secret came out that Flowers had built the first large-scale electronic computer. During his lifetime (he died in 1998) he never received the full recognition he deserved. Many history books, even recently published ones, claim that the first electronic digital computer was a well-publicised American machine called the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer). The ENIAC, however, was not operational until the end of 1945, two years after Colossus first ran. British science and British industry suffered as a result of the total secrecy surrounding Colossus during the postwar years.3 Flowers writes bitterly in Chapter 6 of the long-lasting effects of the secrecy. Until the 1970s few had any idea that electronic computation had been used successfully during the Second World War. In 1975, the British government released a set of captioned photographs of the Colossi.4 By 1983, Flowers had received clearance to publish an account of the hardware of the first Colossus.5 Details of the later Colossi remained secret. So, even more importantly, did all information about how Flowers’ computing machinery was actually used by the codebreakers. Flowers was told by the British authorities that “the technical description of machines such as COLOSSUS may be disclosed”, but that he must not disclose any information about “the functions which they performed”.6 It was rather like being told that he could give a detailed technical description of the insides of a radar receiver, but must not say anything about what the equipment did (in the case of radar, reveal the location of planes, submarines, etc., by picking up radio waves bouncing off them). He was also allowed to describe some aspects of Tunny—but there was a blanket prohibition on saying anything at all relating to “the weaknesses which led to our successes”. In fact, a clandestine censor objected to parts of the account that Flowers wrote, and he was instructed to remove these prior to publication.7 There matters more or less stood until 1996, when the U.S. Government declassified some wartime documents describing the function of Colossus. These had been sent to Washington during the war by U.S. liaison officers stationed at Bletchley Park. Even so, a vital report remained classified. 500 pages in length and called General Report on Tunny, this was written in 1945 by three Bletchley Park codebreakers, Jack Good, Donald Michie, and Geoffrey Timms. Thanks largely to Michie’s tireless campaigning, the report was declassified by the British Government in June 2000, finally ending the secrecy. The full report is available electronically on this book’s companion website www.AlanTuring.net/tunny_report. The release of General Report on Tunny made this book possible.8 At last the wartime records were open to inspection, and the whole incredible story of Colossus and the assault on Tunny was ripe for the telling. Declassification meant that the codebreakers, engineers and machine operators responsible for the defeat of Tunny could at last speak freely. Much of this book is in their words. ISBN 0-19-284055-X (Hardcover) ISBN 0-19-957814-X (Paperback)

Footnotes 1 Coombs, Flowers’ assistant, describes the group as “a happy few, a band of brothers”; Coombs, A. W. M. “The Making of Colossus”, Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 5 (1983), pp. 253-9 (p. 259). 2 Flowers in interview with Copeland (July 1998). 3 See ch. 3 of Copeland, B. J. (ed.) Alan Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine: The Master Codebreaker’s Struggle to Build the Modern Computer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). 4 The photographs were released to the National Archives/Public Record Office (PRO) in Kew, Richmond, Surrey (PRO reference FO 850/234). Several of the photographs are reproduced on this website. 5 Flowers, T. H. “The Design of Colossus”, Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 5 (1983), pp. 239-52. 6 Personal files of T. H. Flowers (24 May 1976, 3 September 1981). 7 Personal files of T. H. Flowers (3 September 1981). 8 PRO reference HW 25/4 (vol. 1), HW 25/5 (vol. 2). Copyright © 2010 Jack Copeland

|

Enigma Enigma

Tunny Tunny

Bletchley Park Bletchley Park

Colossus Colossus

Tommy Flowers Tommy Flowers

The Manchester computer The Manchester computer

ENIAC ENIAC

| |